Firm Profile

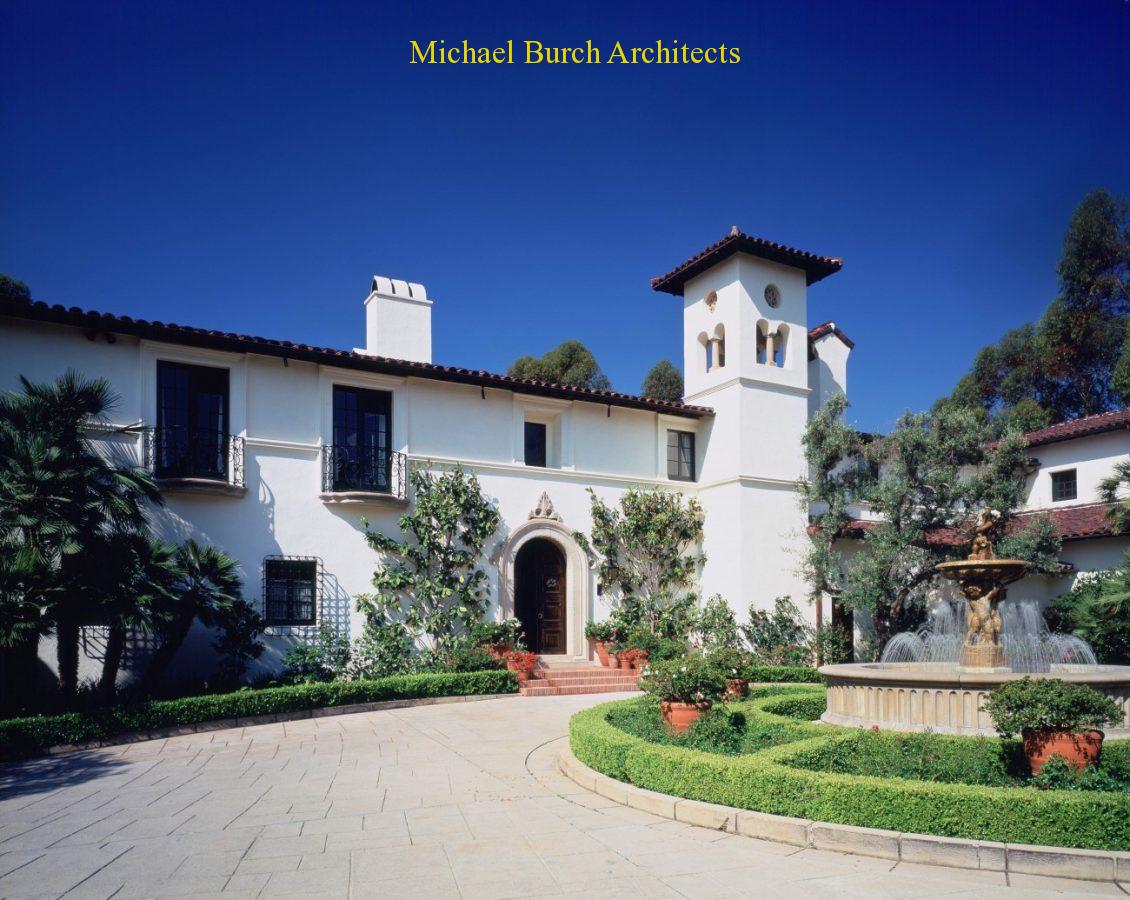

Michael Burch, F.A.I.A., has been deeply committed for 36 years to an investigative practice, at once scholarly and hands-on, that grows out of a passion for Spanish Colonial/Mediterranean Revival architecture. As a 4th generation Southern Californian in the building arts, he is intimately immersed in its architectural traditions and is sought after by clients who share his passion for beauty and romance in buildings, which look and feel as if they have always been there. He refers to his work as “A Return to Authenticity.” Michael has traveled extensively for inspiration (over 90 countries), to virtually all locations in the world where Spanish and Mediterranean architecture can be found. The office has compiled hundreds of thousands of reference images. Issues of sustainability are also integral to the designs, based on vernaculars going back over a thousand years in climates similar to Southern California’s. His work can be found as far away as Hawaii and South Africa.

Michael received his architectural education from the University of California, Berkeley (A.B.) and Yale (M.Arch.). His team consists of Diane Wilk, AIA (B.S.Arch., USC & M.Arch., Yale) and Agnieszka Kaleta Lopez (M.Arch.Eng., Silesian Technical University). The size of the office, allows for his hands-on attention with every client.

Since founding his practice in 1986, he has done extensive community service - chairing South Pasadena’s Planning Commission and Design Review Boards and drafting the city’s General and Specific Plans and Zoning Code. Michael has also been continually active in architectural stewardship, including initiating the cities of La Cañada Flintridge and Indian Wells adoption of the Mills Act, a California property tax incentive program that promotes the stewardship of historic structures. He has personally undertaken the restoration of a number of significant historic properties, including fighting a decades long battle to have Rudolf Schindler’s Grokowsky House historically designated and restored by the California Department of Transportation. He has most recently completed the restoration of the Cavanagh Adobe in Indian Wells, a property that is one of the oldest homes in the Coachella Valley and eligible for the National Register.

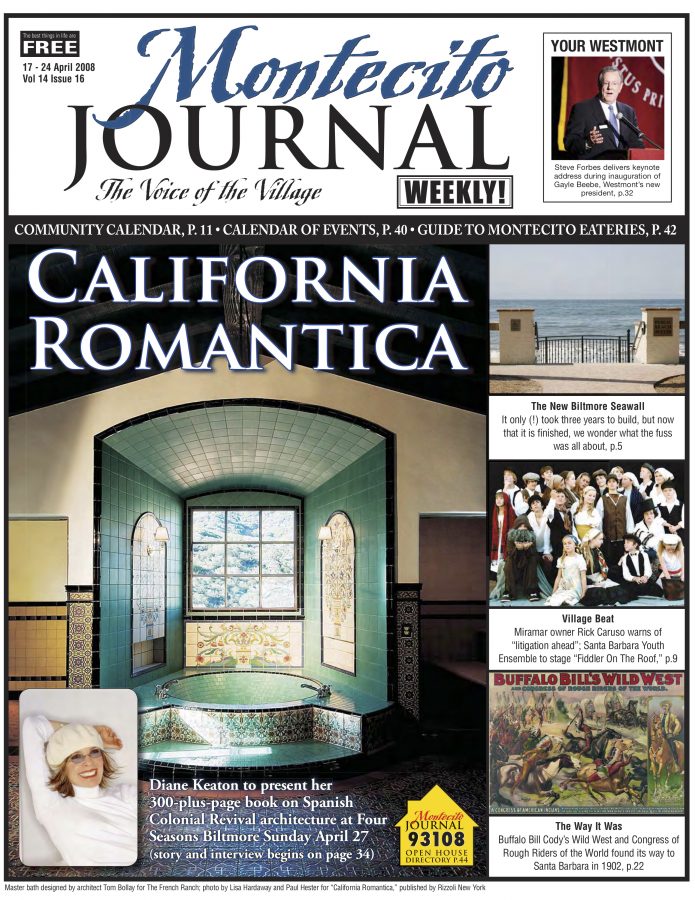

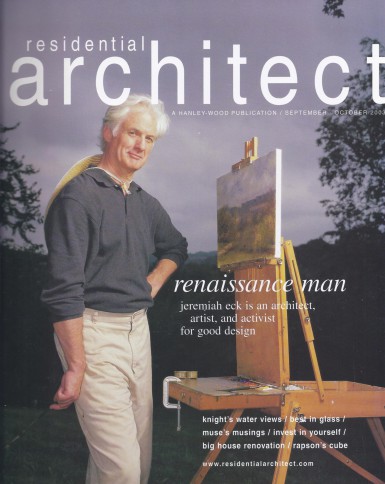

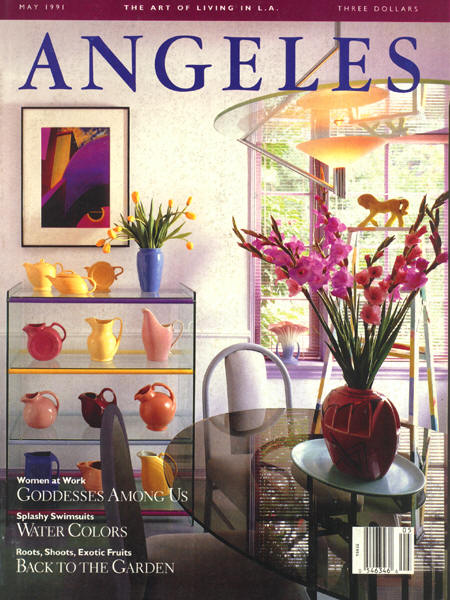

Michael’s work has been featured widely in print, including over 20 books and catalogues (8 by Rizzoli International) and dozens of national and international periodicals. He advocates for stylistic inclusion and diversity by the profession, media and academia. His recent talk to the ICAA-Philadelphia has been viewed over 19,000 times and gains 1,000 new views each month. His outreach to traditional architecture circles is complemented by repeated talks at Palm Springs Modernism Week, where he explores the connections between Modernism and the Spanish Colonial Revival. He is also sought after to lecture to the American Institute of Architects and recently received an invitation to present a T.E.D. talk. Michael has been a lifelong advocate for raising the awareness, standards and expectations of the Classical Tradition and the Spanish Colonial/ Mediterranean Revival Style, both nationally and internationally through books, talks and in academia. He has taught design at Yale, USC and UCLA.

In addition to publications, talks and teaching, Michael’s work has been exhibited at numerous venues. He is a recipient of a Getty Grant for researching Spanish Colonial Revival Architecture and is responsible for initiating the Getty exhibit for Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA,“Myth & Mirage: Inland Southern California, Birthplace of the Spanish Colonial Revival.” Michael has further advanced the standards for architecture and practice through international influence. He has exhibited, by unsolicited invitation, at four recent Venice Architectural Biennales, the only architect specializing in the Spanish Colonial/Mediterranean Revival to ever participate.

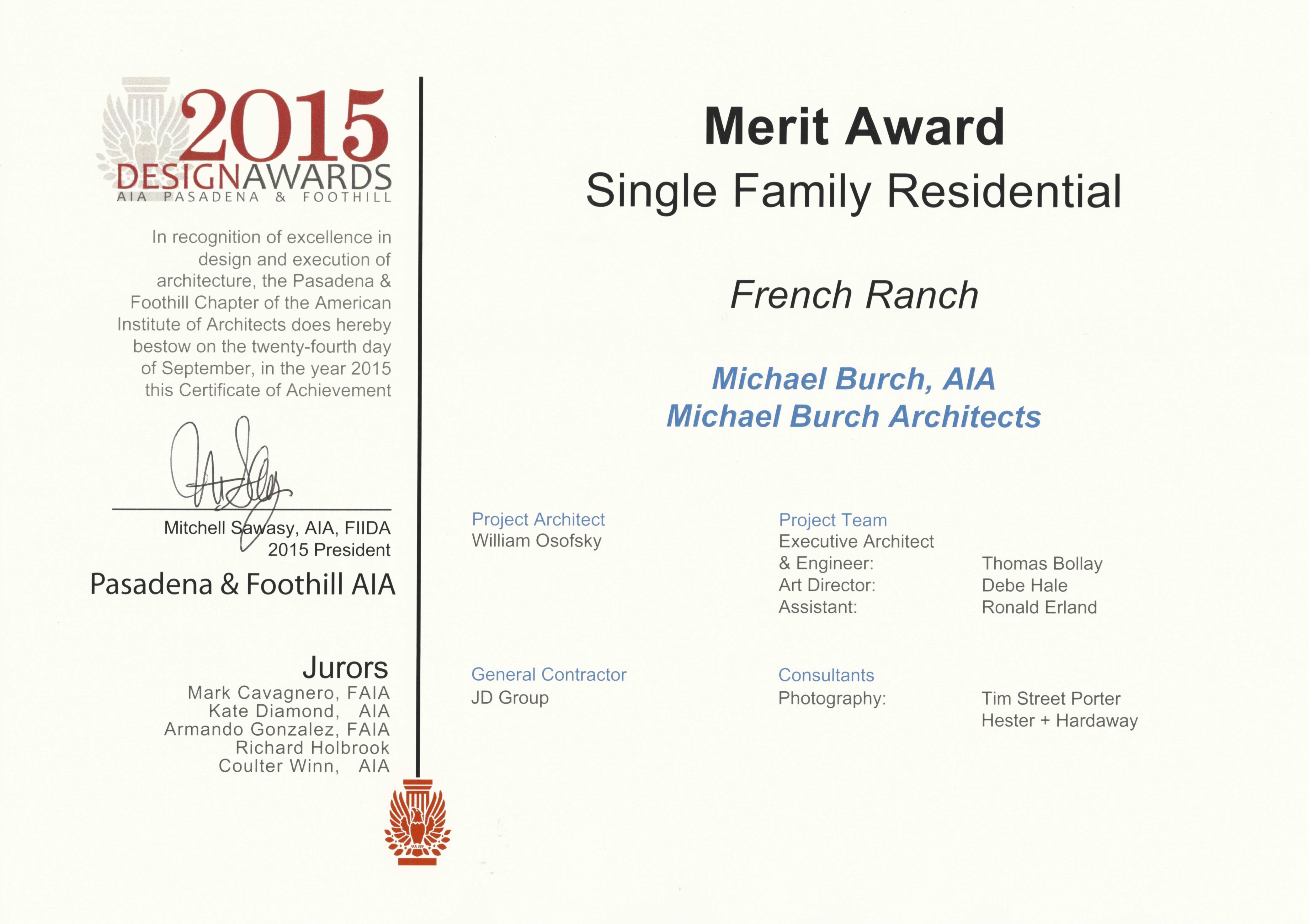

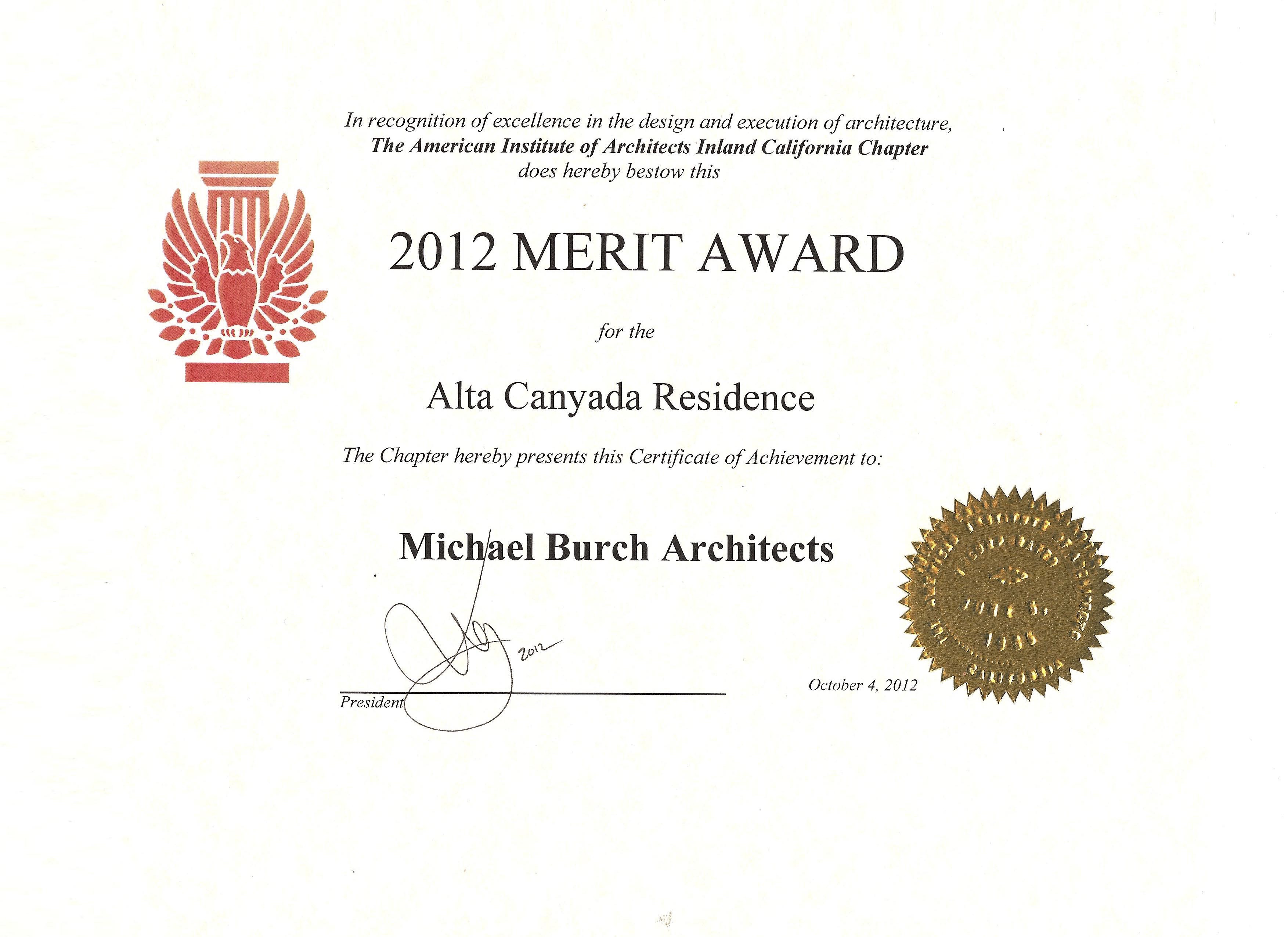

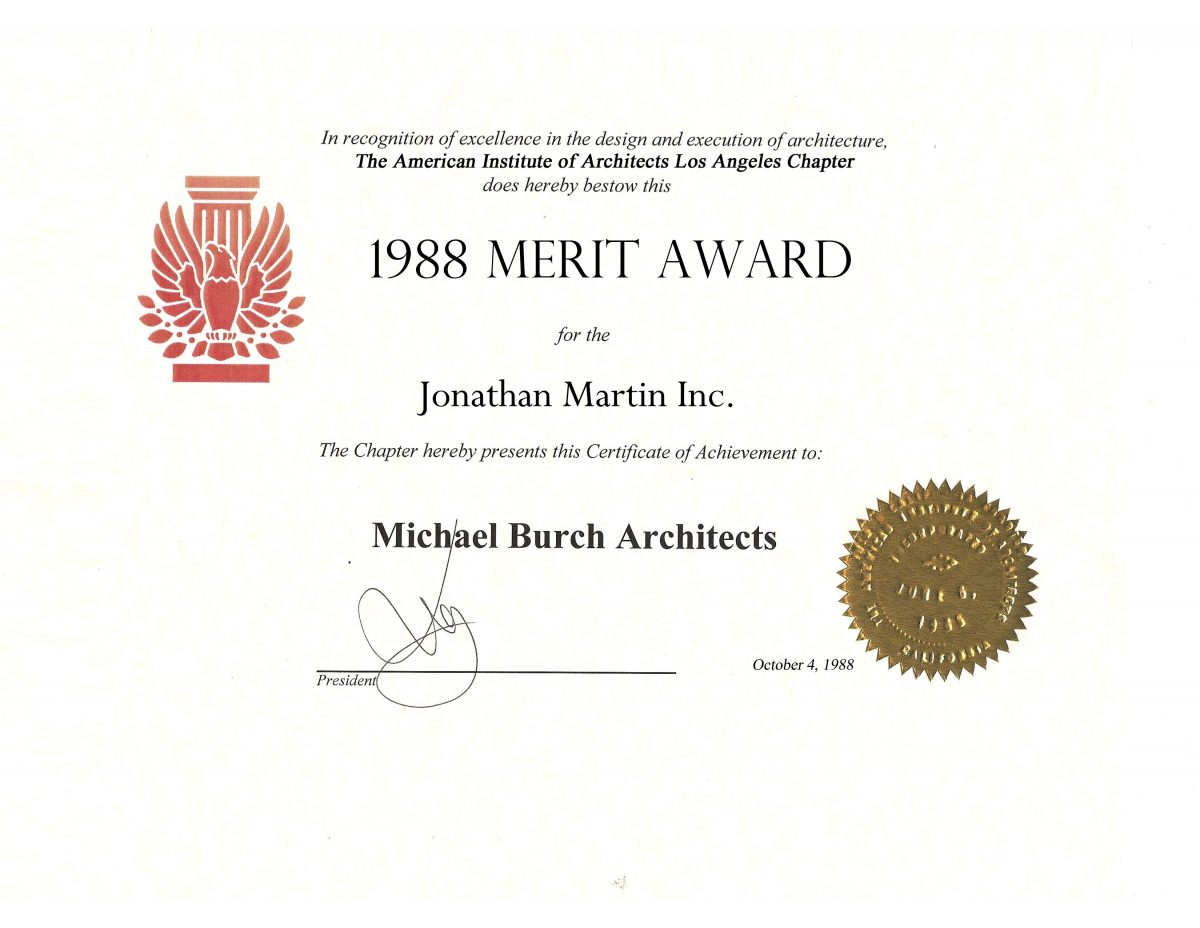

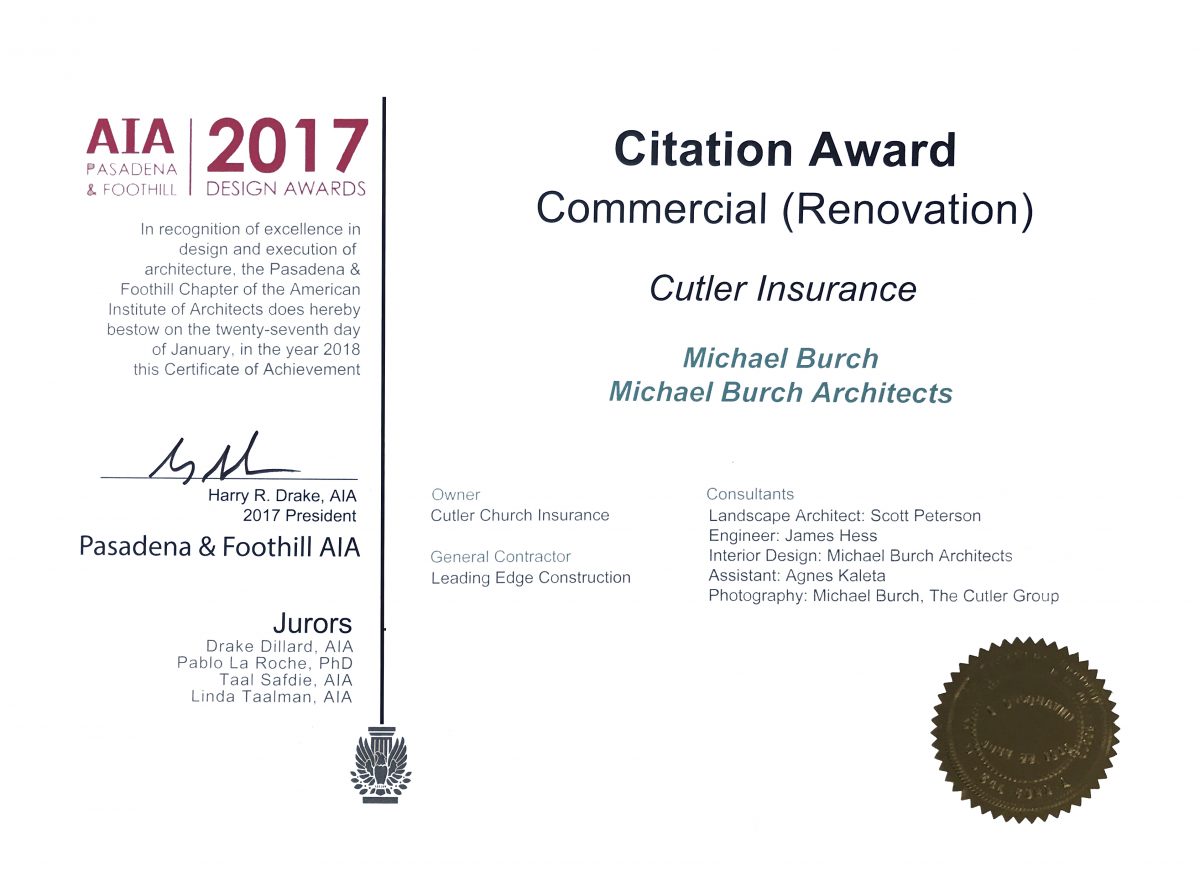

His efforts have received broad national recognition: by the ICAA, with two Julia Morgan Awards; by the Palladio Awards (the sole national award that recognizes traditional architecture) with three honors; and by the American Institute of Architects with numerous awards for design excellence. Michael is also one of the rare classical/ traditional architects to be made a Fellow by the American Institute of Architects, their second highest honor. He has been described as “the greatest living practitioner of the Spanish Colonial/Mediterranean Revival,” by the widely travelled architect and author Stephen Harby, Fellow of the American Academy in Rome and Lecturer at Yale University (Period Homes Magazine). Michael’s work has also been referred to as “breathtaking in its sophistication & beauty” by Aaron Betsky (ARCHITECT: The Journal of the American Institute of Architects).

While Michael also works in other Classical and traditional styles, including Palladian, French Norman and Colonial, he is primarily sought for his expertise in the Spanish Colonial/Mediterranean Revival. With his unique national and international recognition as a master of the style, his work honors and extends the tradition, raising both public and professional expectations.

MICHAEL BURCH, FAIA

DIANE WILK, AIA

AGNIESZKA KALETA-LOPEZ, Associate AIA

Michael Burch works closely with his partner, Diane Wilk, AIA and Agnieszka Kaleta Lopez, as part of an architectural team focusing on giving personalized attention to every client.

Michael Burch (BA, University of California, Berkeley and MArch, Yale) has been described as “the greatest living practitioner of the Spanish Colonial/Mediterranean Revival” (Period Homes Magazine). Michael is a member of the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows - “AIA Fellows are recognized with the AIA’s highest membership honor for their exceptional work… architectural excellence… [and] significant contributions to... architecture and the profession." (AIA College of Fellows). Michael has taught architecture at Yale, the University of Southern California and UCLA.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Burch

Diane Wilk AIA (BSArch, USC and MArch, Yale) was formerly the Director of Graduate Programs in Architecture & Urban Design at the University of Colorado, where, as a tenured faculty member, she taught design, drawing and architectural history. Diane also served as visiting critic at Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Syracuse University and the University of California, Berkeley. In addition to teaching, Diane has published books and articles on architectural and landscape history. She is Director of Research for the firm.

Agnieszka Kaleta-Lopez (MArchEng, Silesian Technical University) joined Michael Burch Architects in 2002. Agnes has both academic, technical and computer-aided design experience. She left her position at the Technical School in Zywiec, Poland, where she taught design, technology and history of architecture, to join Michael Burch Architects.

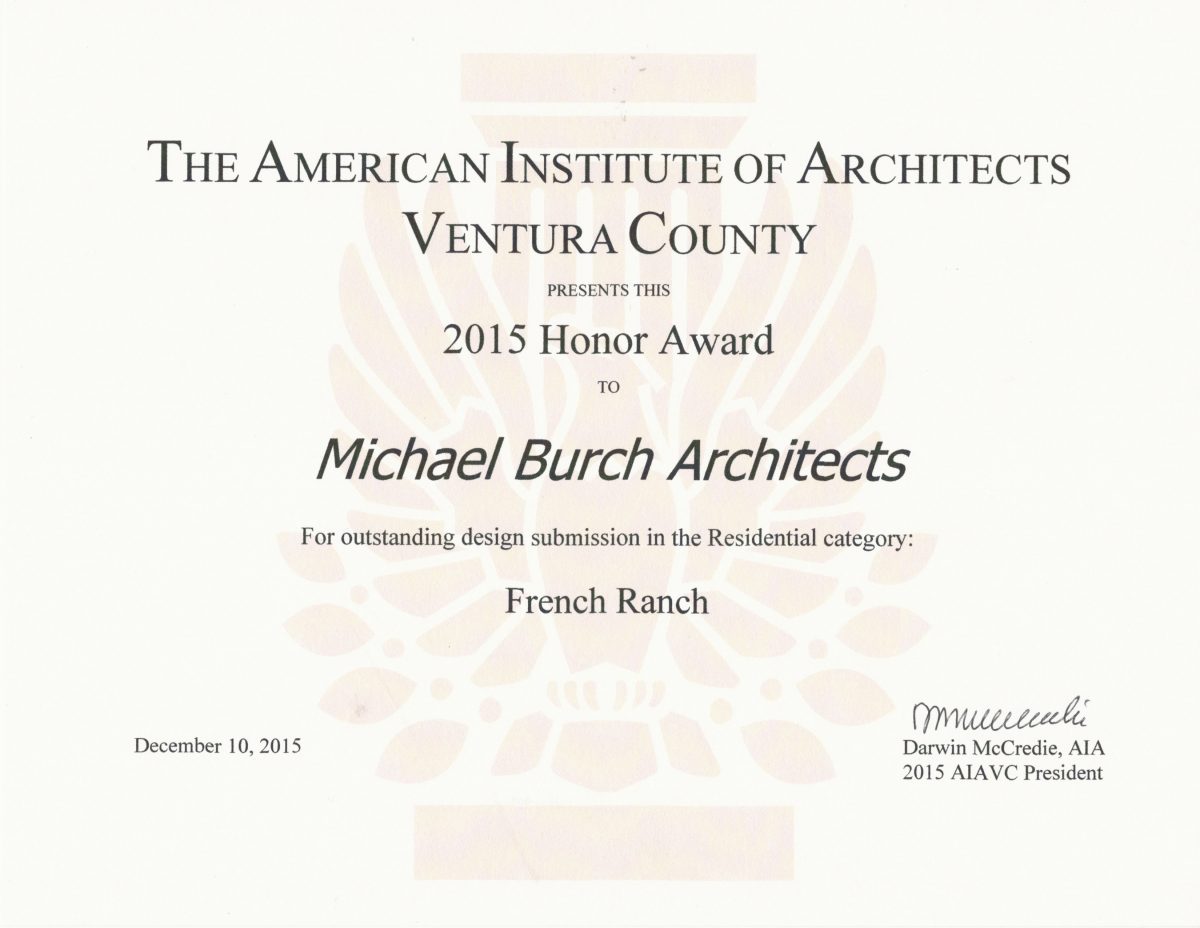

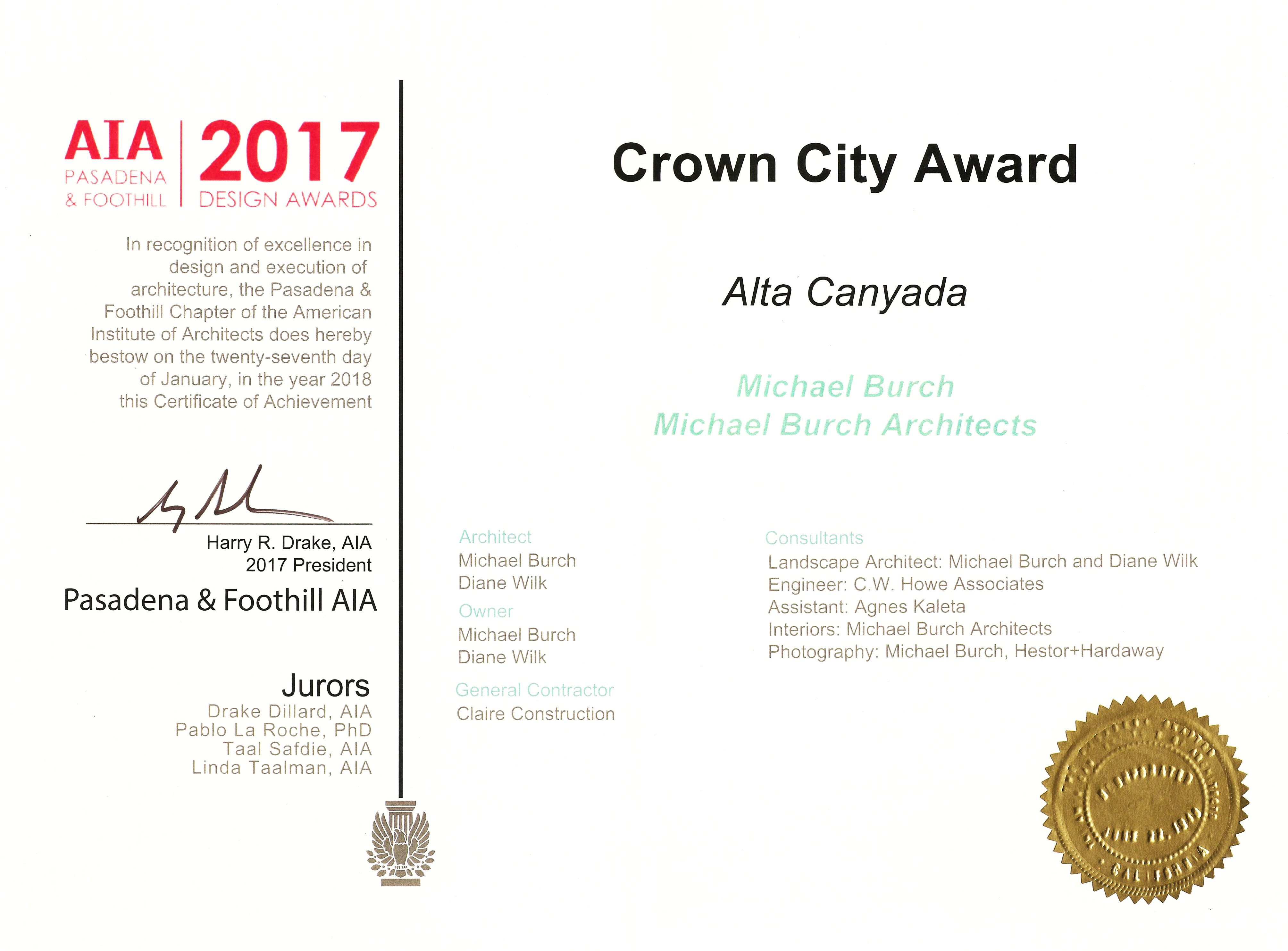

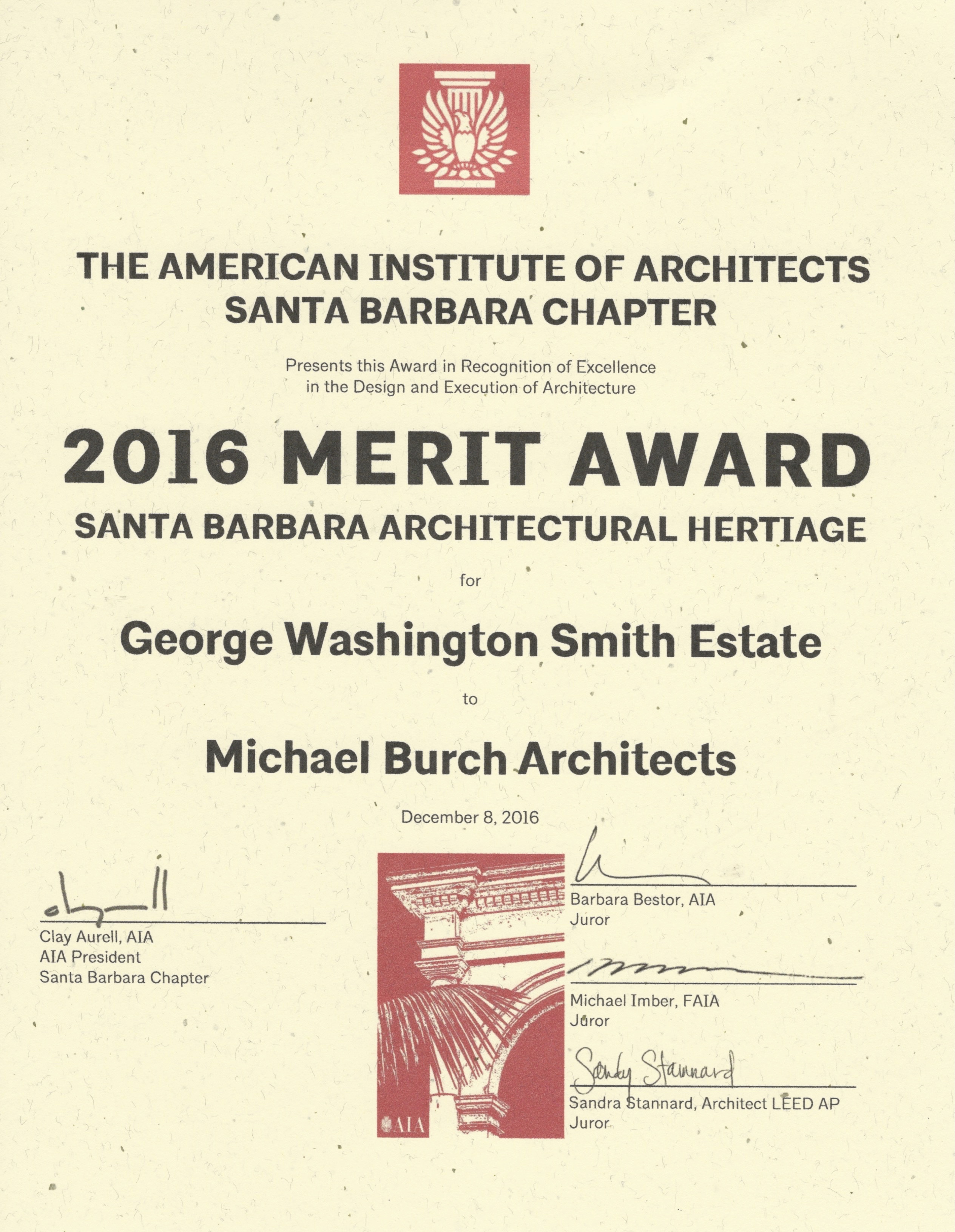

The firm’s work has been featured widely in print, including 20 books and catalogues (9 of which are by Rizzoli International books) and numerous national and international periodicals, including Architectural Digest, Town and Country, and Veranda. Michael Burch is sought after to lecture to the American Institute of Architects and historical societies on the Spanish/Mediterranean architectural tradition, most recently during Modernism Week in Palm Springs, where he described the “romantic modernism” of the Spanish Colonial Revival. The firm has been also been honored with dozens of architectural awards: two international awards, four national awards including three Palladio Awards (the sole national award that recognizes traditional architecture), over a dozen American Institute of Architects Awards and several regional awards. Michael and Diane are also recipients of a Getty Grant for researching Spanish Colonial Revival Architecture and are responsible for initiating the Getty exhibit for Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA,“Myth & Mirage: Inland Southern California, Birthplace of the Spanish Colonial Revival.” Examples of the firm’s work can be found as far away as Hawaii and South Africa. The firm has also been invited to exhibit at the past four Venice Architectural Biennales, the wold’s foremost architectural exhibition.

NATIONAL AWARDS

2014, 2016 & 2018 Palladio Awards

Alta Canyada

French Ranch

Carolwood

AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AWARDS

OTHER AWARDS

INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

CONTINUITY IN MEDITERRANEAN ARCHITECTURE

16th INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURAL EXHIBIT, LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2018: Palazzo Bembo, Venice, Italy

THE TIMES THEY ARE A CHANGIN'

15th INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURAL EXHIBIT, LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2016: Palazzo Mora, Venice, Italy

I GET AROUND: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ARCHITECTURAL FUNDAMENTALS - MISSION TO MODERN

14th INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURAL EXHIBIT, LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2014: Palazzo Mora, Venice, Italy

CALIFORNIA SPANISH ARCHITECTURE: YESTERDAY AND TODAY

13th INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURAL EXHIBIT, LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2012: Palazzo Bembo, Venice, Italy

NATONAL EXHIBITIONS

INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE AND ART, SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CHAPTER TENTH ANNIVERSARY EXHIBIT 2014

BOOKS

PERIODICALS

STYLE GLOSSARY

LATE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES:

The Hispanic Tradition (ca.1770s-1850s)

The mission churches built in Southern California were provincial adaptations of late neoClassic designs primarily of Mexico. Since these church buildings were designed by untrained priests, they often mixed the elements of the neoClassic with earlier Churrigueresque features or with other remembrances which the early fathers brought with them. As in any remove provincial area, the design of these church complexes was tightly conditioned by available resources - limit or non-existent skilled labor, available materials and finally the desire to create a church as rapidly as possible. In the more sophisticated examples, domes, vaulting, and carved stonework occurred. Bell towers, usually of the tiered variety, occur singly or in pairs. One of the most common elements was the long, low arcade with just a slight suggestion of piers supporting the springs of the arches. The adobe style is, in a sense not a style at all. It was simply the direct, logical manner of constructing secular buildings. These were normally one room wide, with the rooms arranged in a row, side by side. The width of a room was determined by the available length of the timbers. Roofs were flat, shed, or gabled. They were covered with asphalt and later with tile. Exterior and interior walls were cover with white lime cement as soon as it was available and could be afforded. Floors at first were of packed adobe, later of tile, and finally of wood joists and flooring. The more elaborate of these Hispanic houses were L or U plans; very few were large enough to form a complete square forming an enclosed patio. Window and door openings were at first kept at a minimum; only with the coming of the Yankee and saw mills were glass (usually double-hung) windows and paneled wood doors made available. The coming of the Yankee brought other changes. Most exterior porches found on adobe houses are a later addition (generally after 1820). Other ‘innovations,” introduced around the min-19th century, were wood clapboard sheathing, wood shingles, and fireplaces. The Yankee additions often transformed the Hispanic adobe buildings into something which was vaguely Greek Revival or, as it is often labeled, Monterrey (for the Monterey style see Greek Revival).

MID 1800s-1900:

Greek Revival (Monterey) style (ca. 1840s-1860s)

The arrival of the Yankee in California in the 1850s and 60s came at the very end of the popularity of the Greek Revival elsewhere in the country. As a fashionable form it ceased to be important in the larger urban areas of the East after 1850, although it should be noted that it continued as a provincial style in the rural/small-town East well on into the 60s. Many examples which we loosely label as Greek Revival are, in fact, a late carryover of the ca.1800 Federal style. The Greek Revival as manifest in California normally conjures up examples of the Monterey style - two story buildings, generally with walls of adobe, cantilevered second floor balconies (or two-story porches supported by simple thin square posts), double hung windows and perhaps an entrance with sidelights and a transom light. These houses represent the additions of provincial Yankee and Federal wood details to the earlier Hispanic adobe. The Monterey style occurs throughout California, and is in no way restricted to the Monterey area. Nor is it even specifically Californian, for 19th century examples are found in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico as well.

Characteristics:

rectilinear, gabled roof volumnes, one or two stories, horizontal in character, roof at low pitch

symmetrical, balance plan and disposition of windows and doors (the side-hall plan is simply one-half of a symmetrical unit)

wide entablatures, occasionally with dentils

gable ends form classical triangular pediment with horizontal roof eave/cornice carried across gable end

frequent occurrence of engaged piers at corner

flat or pedimented windows and doors

use of Doric (occasionally Ionic) columns

entrances with side and transom lights

use of narrow wood porches and second floor balconies

roofs often covered with wood shingles

1890s - 1920s

Mission Revival (ca.1890-1912)

The Mission Revival began in California in the early 1890s and by 1900 examples were being built across the country. Its high point of popularity was in the ten year period 1905-1915. As a style it was used successfully for a wide variety of building types, ranging from railroad stations and resort buildings to schools, service stations, apartments and single family dwellings. As a style it easily lent itself to available methods of construction, from stucco and wood stud to hollow tile and reinforced concrete. Since it relied on only a limited number of stylistic elements, it could readily be organized to satisfy new functional needs.

Characteristics:

white, plain stucco walls

arched openings - usually with the pier, arch and surface of buildings treated as a single smooth plane

tile roofs of low pitch

scalloped, parapeted gable ends

paired bell towers, often covered with tile hip roofs

quatrefoil windows (especially in gabled ends and accompanied by surrounding cartouches)

occasional use of domes

ornament when present case in terra cotta or concrete; patterns often Islamic and Sullivaneque

1900-1940s

Spanish Colonial Revival (1915-1941)

The Spanish Colonial Revival was a direct outgrowth of the earlier Mission style, and examples were built as early as the 1890s in Southern California. The symbolic beginning of the revival was the San Diego Fair in 1915 and the buildings designed for the fair by Bertram G. Goodie and Carleton M. Winslow. By the 1920s it became the style for Southern California. Hispanic or, as they were often called, Mediterranean designed were employed for the full range of building types.

Many communities adopted the style. The term Spanish Colonial Revival actually entails a number of related styles - including the Italian of northern Italy, the Plateresque, Churrigueresque and neoClassic of Spain and here colonies, and the Islamic from North Africa. Its most formal exercises looked to Italian examples while the Andalusian was employed for informal designs. The acknowledged master of the style was architect George Washington Smith. The style’s greatest period of popularity was 1915-1930.

Characteristics:

stucco surfaces which predominate over the openings

low pitched tile roofs

limited number of openings (best if deeply cut into the wall surfaces)

closely related to outdoors through the use of French doors, terraces, pergolas

gardens designed in a formal axial manner

use of decorative ironwork for windows, doors, balconies and roof supports

glazed and unglazed tile used for walls and floors

commercial buildings generally organized their facades in deep-set vertical bands (with windows and spandrels recessed)

Plateresque and especially rich Churrigueresque ornament of cast concrete or terra cotta occurred in many commercial buildings, and occasionally in domestic designs

Pueblo Revival (1900-1930)

The Pueblo Revival was based upon forms developed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico. Surprisingly it was never a widely used style in Southern California, though features of the style like projecting visas and parapeted roofs were employed as elements on what otherwise was Spanish Colonial Revival design. As a style it remained exotic for the Southland. Examples of the style are primarily residential.

Characteristics:

general profile low, earth hugging

thick adobe-appearing walls, sometimes fake, sometimes real

adobe walls extend vertically as horizontal parapet, usually with edge of parapet curved to suggest the handmade feeling of adobe architecture

roofs flat and invisible behind parapets

rows of projecting vigas

tree trunks for porch columns

brick used for terraces, porch and interior floors

small windows, usually of casement type

oven type corner fireplaces

Monterey Revival (1928-1941)

The Monterey Revival provided a fusion of Spanish and the Colonial, and even in some instances with the Regency. The style was almost exclusively limited to domestic architecture, though occasionally found in small shops and motels. Its first examples tended to be more Spanish, the later examples more Colonial or Regency. Its two most gifted proponents in the Southland were Roland Coate and H. Roy Kelley.

Characteristics:

single two-story rectilinear volume; occasionally with wings

stuccoed surfaces; in some examples board and batten used especially to sheath second floor

low pitched gable roof covered in most instances with wood shingles

projecting second floor balcony with simple wood supports and wood railing

“Colonial” entrances with paneled doors, sidelights, fanlights, paneled recesses

double hung wood windows with mullions; occasional Greek Revival detailing of wood frame

“Colonial” interior detailing - fireplaces, built-in cupboards, wood paneled walls, etc.

1940s - PRESENT

California Ranch House (1935 - present)

The California Ranch House developed out of the turn-of-the-century Craftsman bungalow and the Period style bungalows of the 1920s. The ranch house is a single floor dwelling, low in profile and closely related to terraces and gardens. Its specific historic images were both the 19th century California adobe house and the 19th century California single-wall board and batten rural farm building. The characteristic ranch house did and still does imply a variety of historic images, but the classic design mingles modern imagery with the Colonial. Los Angeles designer Cliff May can be considered the author of this informal style of suburban residential design.

Characteristics:

single floor dwelling, composed of informal arrangement of volumes

low pitched hip or gable roof with wide overhangs

sheathed in stucco, board and batten, shingles, clapboard, or a combination of one or more of these

windows often treated as horizontal bands

glass sliding doors lead to covered porches, terraces or pergolas

interior spaces open, and of low horizontal scale.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Excerpts from A guide to Architecture in Los Angeles & Southern California by David Gebhard and Robert Winter, pp684-705

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

“In the twentieth-century American architectural scene, there has been only one brief period of time and only one restricted geographic area in which there existed anything approaching unanimity of architectural form. This was the period, from approximately 1920 to the early 1930s, when the Spanish Colonial or the Mediterranean Revival was virtually the accepted norm in Southern California.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- David Gebhard, introduction to George Washington Smith, 1876-1930, the Spanish Colonial Revival in California, and Exhibition, November 17 - December 20, 1964, Held at The Art Gallery, University of California, Santa Barbara.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-